Part I: West?

The legend has it that when Mark Twain was visiting his home state of Missouri, he was approached by a young man. The former Samuel Clemens had by this point already fully become “Mark Twain,” the white-suited, Connecticut comedian who would eventually receive an honorary doctorate from Oxford University. He is immediately recognizable, a 19th-century media figure functioning as his own brand and spokesman at the same time. Yet Twain’s field still is literature, and the young man who approaches reckons that both of them are the best in their respective lines of endeavor. While Twain knows himself and his enterprises, he is unaware of the young man and his labors. “And who are you?” Twain inquires. “Jesse James,” the man answered. And nothing more needed to be said.

It does not matter if this story is true or not, but the point of it may be lost currently. What the exchange really shows is that at a particular moment in time, two of the most famous men in the country were both native Missourians. Twain, due to inclination and travel, would be claimed by various regions of the United States and indeed the whole world, but Jesse James was and remained Missouri to the bone. Yet many do not know or understand that James was a Missourian, and this misunderstanding of the past is generally Hollywood’s fault. Even when Oklahoma native and Missouri-raised Brad Pitt played Jesse James in 2007, the truth was not advanced. When I first saw The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, I was regularly distracted by the wind wafting through the stands of spruce trees. Spruce? Missouri? Most of the film looked like Canada because that’s where it was mostly filmed.

Details like these may seem inconsequential, but the tendency is disturbing because the removal of the past from its specific place renders the past even more foreign. I recognize that filmmakers are not historians and that they are making choices based on visual needs rather than offering an interpretation of apparent facts. The jobs are different, but sometimes filmmakers believe it their role to correct false views of the past, often making claims of fundamental veracity. The quote attributed to President Woodrow Wilson about the racist masterpiece Birth of A Nation is true about filmmaking itself even though it is not true about Birth of A Nation. Wilson, after seeing the film screened at the White House, reputedly said that the movie was “like writing history with lightning” and indeed the version of the past that Birth of a Nation presented subsequently would do great damage in American life. Film as an exercise is not about being true, but its power is undeniable, and we “know” the past from film more than from any other source. As a result, the wrongness of film in terms of history can create genuine problems, and the life of Jesse Woodson James is a prime example.

Jesse James was beloved by Hollywood from the beginning. His son, Jesse Edward James, played his father twice in two silent films in 1921 taking the screen name Jesse James Jr. Since then there have been at least 50 films featuring Jesse James either in the title, as a subject or as a character. The big film was Jesse James made in Hollywood’s greatest year of 1939. The film featured Tyrone Power and Henry Fonda as the Brothers James, and for accuracy sake it was filmed on location in Missouri, but due to population growth, the points of Kansas City, Kearney and St. Joseph where James spent much of his time were bypassed for scenic rural spaces in Missouri’s southwest corner. In other words, Jesse James moves to the Ozarks though he was born in Clay County. Even when Hollywood tries really hard, it rarely can do the past right in terms of the specificity of place. The film should be commended for putting James in Missouri at all, for subsequent films would position him in the nebulous Old West of Hollywood geography, usually and not surprisingly resembling southern California.

Among the multitudes of Jesse James movies, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford is generally considered and should be regarded as one of the good ones. It is, but it lacks so much compared to its source novel by Ron Hansen. For me as a reader, Hansen’s book is tremendous, and Hansen firmly places James in his time and place. And James as Old West hero lived on the 19th-century frontier, except that at time, the West started on the edge of the Kansas border. Here is just one description of James as he lived anonymously on Woodland Avenue in Kansas City, Missouri in 1881:

He was born Jesse Woodson James on September 5th, 1847, and was named after his mother’s brother, a man who committed suicide. He stood five feet eight inches tall, weighed one hundred fifty-five pounds, and was vain about his physique. Each afternoon he exercised with weighted pins in his barn, his back bare, his suspenders down, two holsters crossed and slung low. He bent horseshoes, he lifted a surrey twenty times from a squat, he chopped wood until it pulverized, he drank vegetable juices and potions. He scraped his sweat off with a butter knife, he dunked his head, at morning, in a horse water bucket, he waded barefoot through the lank backyard grass with his six-year-old son hunched on his shoulders and with his trousers rolled up to his knees, snagging garter snakes with his toes and gently letting them go.

What is extraordinary about this description is that Hansen is using real facts to create this character, an actual being born in Missouri who fascinates more than any of the renditions of him. Hansen continues, and his James embodies what was true about the man then and now: he is an object of utter fascination. We have never gotten enough of Jesse James, and Hansen shows us why:

He could intimidate like King Henry the Eighth; he could be reckless or serene, rational or lunatic, from one minute to the next. If he made an entrance, heads turned in his direction; if he strode down an aisle store clerks backed away; if he neared animals they retreated. Rooms seemed hotter when he was in them, rains fell straighter, clocks slowed, sounds were amplified: his enemies would not have been much surprised if he produced horned owls from beer bottles or made candles out of his fingers.

He was a star. A celebrity. His very magnetism is what draws his assassins to him and sponsors the bounty on his head approved by the sitting Governor of Missouri. It is no surprise that his son entered moving pictures, nor is it surprising that Robert and Charley Ford became theatrical players redoing the assassination over and over for the New York stage. James was show business from the beginning, and he attractively combined politics and criminality. The real James was also prettier than Brad Pitt; he reputedly was dressed as a girl as a decoy before a guerilla raid. The real James has always been more interesting than the fakes, and the fakes showed up as soon as he was dead, for like most deceased celebrities, he was granted an afterlife subsequent to his supposed burial. Jesse James was the first almost immortal star — the prototype for another country boy who made good, Elvis Presley. Just as Elvis sightings have continued long after 1977, Jesse James was still being spotted well into the 20th century.

Yet Jesse’s fame renders him universal and therefore divorced from his particulars, but to excise the Missouri from Jesse James, either for poetic or artistic license, is to miss the man altogether. There could not be a Jesse James without a Missouri. He was a product of a specific time but also a very specific place. He was made by the conflict on the Kansas-Missouri border. He was made by the debate over slavery and secession. He was made by frontier violence but that frontier we now know as State Line Road and not the Rocky Mountains. The West we imagine, in most cases, is from the movies. The actual west of the 19th century, the one we see as epic, took place predominantly between the Mississippi and the western edge of the High Plains. That was the west. The cattle drives that invented our idea of the cowboy first went to Missouri and then to Kansas. The problem is that this area now has been altered, or it has been viewed as insufficiently scenic, and so in terms of collective memory, it does not exist. It is just another case of the middle of the nation being erased due to coastal vision.

Another novel that is better than its movie adaptation is Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man. What I found so great about this book is that Little Big Man the character spends most of his time on the Plains; this shouldn’t be surprising since he is adopted by the Cheyenne, a Plains tribe, but we are so used to the emblematic headdress and horse Indians being in John Ford’s Monument Valley of Arizona that we can no longer see the past of the Old West being in its real place. Little Big Man also spends quality time in what is now the River Market area of Kansas City. Who does he befriend there? Wild Bill Hickok. Is Berger wrong? Was this the West? Yes. Wild Bill Hickok had his first law enforcement job in what is now suburban Johnson County, Kansas and his first real Old West gunfight in Springfield, Missouri. He also, like Jesse James, participated in the Kansas-Missouri Border War except that unlike the Confederate James, Hickok fought for the Union. While some know that Frank and Jesse James and the Younger Brothers fought as Missouri Confederate guerillas, few know about the Kansas Union veterans. But some of them became famous too, like Buffalo Bill Cody and Wild Bill Hickok, Kansas Yankees both. It is interesting that some of the famous figures of the Old West were both part of the conflict along the Kansas-Missouri, but this fact of service is often ignored or considered insignificant. The veterans from the winning side went into government contracts or law-enforcement, and the losers went on to rob banks and trains. Either way, they all chose violence because it is what that particular state line taught them. That they lived near the 95th meridian, while some say the West does not start before the 100th, is another issue entirely, but it is apparent that with Manifest Destiny, lines became blurred. We may span from sea to shining sea, but not to recognize that much of what we call “western” took place in the middle of the nation is not to understand the real past and the stories that we tell ourselves.

Part II: South?

To understand Jesse James, it is essential to understand that he argued, and his supporters believed, that his robberies were committed in a political context. The argument behind the James-Younger gang was that specific banks and trains were robbed: their violence was not intended to be random. Rather their actions were a continuation of their early Confederate guerilla training under the leadership of William Quantrill and Bloody Bill Anderson. T.J.Stiles in the great book Jesse James: The Last Rebel of the Civil War articulates this point fully: Jesse James was still fighting as a Confederate guerilla long after the war was through and his robberies were seen as heroic by some because they saw him as an advocate for their political position. While James continued in his role as a Partisan Ranger, other Missourians from regular Confederate forces proved equally recalcitrant. The old saw about the South that “they’re still fighting the war down there” proved true in Missouri in ways that it did not in other places; while the South signed away its apparent sovereignty at Appomattox, some Missouri Confederates refused to capitulate, and instead they chose to go even farther south to Mexico rather than live under Federal rule.

General Jo Shelby and his Iron Brigade are a great story if nothing else, and the recent book General Jo Shelby’s March by Anthony Arthur tells it well. Missouri Confederates, unhappy with the actions of Virginia’s eastern establishment, decided to go freelance, and they saw the best chance at the continuation of their values down in Mexico. They picked the side of Emperor Maximilian, a bad choice, for he would be eventually executed by Mexico’s legendary president, Benito Juarez. So Shelby and his men in effect lost twice, but there is a certain glamor in never surrendering, with the Iron Brigade resembling the Anabasis of Xenophon, Greek soldiers abandoned in Persia who had to fight their way back home. Shelby maintained his appeal in Missouri even after he recanted his Confederate position with the claim that “John Brown was right.” He ended his days as a U.S. Marshal for western Missouri after being appointed by President Grover Cleveland. Jo Shelby’s march was later made into a 1969 film called The Undefeated with the names and facts changed. I have never had the patience to watch the film all the way through because they fictionalize too much, but for the trivia fan, it is the only on-screen pairing of John Wayne and Rock Hudson. Again, the real story is more interesting than the Hollywood embellishments, but this has been stressed previously.

While Jesse and Frank James did not go south with Shelby, they did manage to maintain their war in Missouri. This should not be surprising: in Kansas and Missouri, the Civil War started before Fort Sumter, so continuing the war after Appomattox is only natural. Many question the premise that politics rather than gain motivated the James-Younger gang, but politics, opportunism and theft were often united by both sides on the Kansas-Missouri border conflict. Hollywood has loved this particular form of the Civil War even if it has not portrayed it effectively. Literature has loved this battle too, with film adaptations following soon after.

The best book to treat the topic is True Grit by Charles Portis, just because it is such a great book. Though Portis presents a manhunt in Indian Territory, it is led by the legendary Rooster Cogburn, a fictional but plausible former Missouri Confederate guerilla who lost his eye and gained his trademark eye-patch at the Battle of Lone Jack just outside Kansas City. Cole Younger and Frank James make cameos at the novel’s conclusion. The book has been adapted twice with John Wayne as the first and Jeff Bridges as the second Rooster. There are debates about which film is better, but in neither does the land look too much like Arkansas or Oklahoma, the novel’s actual settings.

Following True Grit, The Outlaw Josey Wales starring Clint Eastwood is generally the other Border War favorite. It comes from a novel by Forrest Carter. Carter, who gained additional fame as the author of The Education of Little Tree, was later discovered to be the reinvented Asa Carter, an Alabama segregationist, white supremacist and Klansman. That for a pen name and new identity, Carter took the last name of Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest was not accidental.

Woe to Live On by Daniel Woodrell has been out of print, but the recent Oscar nomination of Winter’s Bone, and the film adaptation of Woodrell’s novel of the same name, is bringing new attention to his work, so Woe to Live On came back in print as of this summer. Its film adaptation, Ride with The Devil, exemplifies many of the problems of depicting the Kansas-Missouri Border War though at least it was filmed in Kansas and Missouri. To begin, most of the characters speak with bad southern accents from an apparently fictional place called Quasi, Alabama: the subtleties of the Missouri rural dialect are definitely missed. Additionally, by the time the movie was made in 1998, our national comfort with a sympathetic portrayal of slave owners had essentially run out. And there’s the little detail of an African-American character riding alongside and participating with Confederate guerrillas in the raid on Lawrence that made some viewers uncomfortable.

But here’s the problem: at least three of Quantrill’s Raiders were free African-American men from Missouri, and according to Edward Leslie, author of The Devil Knows How to Ride: The True Story of William Clarke Quantrill and His Confederate Raiders, two of them frequently attended the Quantrill Reunions where they received warm welcomes and good wishes from their fellow Confederate veterans. If this detail sounds weird, it is because real history is weird, particularly American history, particularly in the Civil War period and particularly along the Kansas-Missouri border. Though the famous L.M.D. Guillaume painting of “The Surrender of General Lee to General Grant, April 9, 1865” shows one noble general calmly eyeing the other noble general, it never got that civilized west of the Mississippi. Along the Kansas-Missouri border it was personal and barbaric, but perhaps even nastier was the fight within Missouri itself, for the state had the dubious privilege of being both a part of the Union and the Confederacy at the same time.

Some do not understand this ambiguity and ambivalence because it makes little sense. For many, Missouri is not in the South in the first place. The true answer is that it is, and it isn’t. In terms of geography, the old Mason-Dixon line runs at the 39th parallel, essentially Pennsylvania’s southern border, and the Missouri Compromise of 1820 claims that though Missouri can enter as a slave state all subsequent states on the Great Plains must be south of the 36th parallel: in other words a slave state must be at the same point north as Arkansas; Indian Territory (Oklahoma) and Texas then can be slave states, but Nebraska and Kansas territories cannot, though the case of Kansas later got complicated. What does this mean? The expanded south after 1820 would not go north of Arkansas, so the border states of Missouri, Kentucky and Virginia would not technically be southern according to this later definition despite being below the Mason Dixon. Of course later Richmond, Virginia becomes the capital of the Confederate States of America and Kentucky like Missouri becomes a provisional Confederate state while also officially staying in the Union.

Yet many of us see Kentucky as southern, but not Missouri, even though their political positions in the Civil War were basically the same and both were considered as Confederate states by the Confederacy itself. Missouri of course is a tall state that goes farther north than Kentucky, but this confuses the issue further, for the cultural southern heartland of Missouri was not in the southern part of the state. The “southern” part of the state culturally known as “Little Dixie” was along the Missouri River, geographically speaking in the state’s west and center. Missouri’s Little Dixie went east from Callaway County to Kansas City on both the northern and southern sides of the river. If this all sounds confusing, it was even more so during the Civil War, when some slave owners remained loyal to the Union and refused to secede, and some free black men became Confederate guerillas. Though Kansas bled, it was defiantly Union upon receiving statehood. In 1861 as the 34th Star, it was the last state to appear on the national flag until the Civil War’s end. Missouri had a hemorrhage of a different kind, a bleeding and set of bad feelings that did not end when the war went away. Anthony Arthur in General Jo Shelby’s March plausibly maintains that Missouri’s feud with itself continued through the death of Jesse James and up until the court trial of his brother Frank in 1882. Frank James was acquitted of all charges. His character witness was General Jo Shelby, and Anthony Arthur claims that Shelby’s defense saved Frank James from the noose. Frank James had rescued Shelby from capture during the war apparently, and the debt had to be repaid.

Part III: Code?

It might disturb some of the urbane in Kansas City, Missouri, that their city was part of a place called Little Dixie. This fact certainly isn’t advertised, but the markers of southern identity are present in Kansas City still and in Missouri as a whole. Few who drive along Ward Parkway pay attention to the fact that the Daughters of the Confederacy have a monument on 55th Street. Nobody seems to say much about the Confederate Infantrymen staring out of the upper windows at Kelly’s in Westport. And few know that there is a monument to the Confederate Dead at Forest Hill Cemetery at Troost and Gregory. It is gigantic in comparison to the other markers in the cemetery. A tall pillar with a life-size sculpture of a Confederate soldier on top, and few in Kansas City know it even exists, but some do because they visit leaving gifts.

I personally discovered it by fluke. I was astonished to see it and to see what it was. Many of the big names of the Missouri Confederacy are present, including General Jo Shelby, and up the hill one of Missouri’s Confederate Senators, Waldo P. Johnson. But what surprised me when I first randomly found these graves was a wreath left at the bottom of the monument coupled with a small Confederate flag. It had snowed, and these items were obscured, but they were present, and they were relatively recent.

So not only is there a Confederate memorial of substance in Kansas City, but it is visited by observant current Confederates. This surprised me, but maybe it shouldn’t have. This activity has been going on for a while, but I thought it had stopped. When I was growing up, we would visit my grandmother’s grave in Raymore, Missouri in Cass County. Raymore is now part of south Kansas City, but then it was just a small town, and the cemetery was sort of out in the country. As a child, I would see small Confederate flags at certain graves which had designations of service in the Confederate army. They were stark in that cemetery but also curious: it was my first understanding that Missouri — or part of it — was in the south. One year we went back and they were gone, replaced with non-controversial U.S. flags, not accurate for the graves, but that’s how times change. Except they don’t.

The idea of the thing we call the Confederate flag fluctuates. It has had different meanings at different times. The first issue is that the “Confederate Flag” is not technically the Confederate flag at all. The original Confederate flag is called the Stars and Bars or First National Flag which was quite similar to the U.S. flag except for fewer stripes and fewer stars since the Confederate States were fewer in number. On the field of battle, the similarity between the U.S. flag and the Stars and Bars created confusion, so the south adopted another flag featuring a St.Andrew’s or X-shaped cross which would then be conspicuously different than the U.S. flag. This X-shaped cross flag, which was sometimes called the Confederate Battle Flag, is the Confederate flag we now know, or think we know.

The problem has arisen that the Confederate Battle Flag has been adopted as an emblem of white supremacists and therefore it has become synonymous with the Nazi flag, since Klan types when they march often like to carry both. If we have any understanding of the current Klan and its adherents, our view is mostly formed from the old daytime talk shows that liked to bring Klansmen on as objects of ridicule. These shows succeeded in portraying individuals who were effectively engaging in self-parody, and for the viewer, a sense of comfort was derived by seeing stereotypes as real. Yet those who presently engage in what I can only call Confederate apologetics are in many cases not fools. From what I have encountered, some of them know their history better than most, even if they happen to view it with selectivity. These individuals who may be Confederate flag supporters are more complicated than the simple broad brush stroke of racism that is applied to them. In my experience, they very much want to stress that their position is not racist, yet they are also aware that their arguments will not convince. They know that the Confederate Battle Flag means racism to many, and racism means ignorance. Though they try to make the claim that the flag is “Heritage, not Hate” they know that many will not believe them. So one way of dealing with the controversy is to use code and let the symbol hide in plain sight, but the use of code demonstrates a lack of stupidity which may make some uncomfortable. It is always easier to see those we might disagree with as idiotic, but when we do so, we fail to recognize why people may support a position in the first place. Whether it is acknowledged or not, the Civil War is still being fought, and failing to explore the complexity of this continued conflict serves the interests of no one.

Code is part of this lingering war, but I am by no means an official scholar of the period. I am just a reader and observer of how we keep working on these narratives that are actually essential to our identity as a nation, but this issue of code seems critical. One item that I have noticed and it may be commonly known is that current southern partisans do not believe in the Civil War itself. From what I have encountered, they do not use the term “Civil War” at all, and instead prefer “The War Between The States.” I don’t know why this terminology is so important, but it seems relatively omnipresent in southern partisan circles. I guess “War Between the States” focuses on the State’s Rights issue, but I honestly don’t know when or why this designation for the Civil War became preferred in these circles. This is just one example of how terminology and symbol play out in a subtle fashion.

Another example of extreme subtlety is the State Flag of Georgia. Many southern states have featured some variation of the Confederate Battle Flag in their state flag, but Georgia’s flag adopted in 1956 was particularly blatant. Changing times called for a reduction of the Battle Flag’s prominence, but eventually this revised flag was changed also. In 2003, Georgia adopted a new flag, and the Confederate flag was nowhere to be seen. Instead the new flag resembles an old fashioned American flag with a blue field, a circle of 13 stars with Georgia’s seal in the center, and two red bands separated by one white. So much for that Confederate flag, except that Georgia’s flag is essentially identical to the Stars and Bars or the original Confederate flag except for the addition of the seal in gold. So Georgia replaced their state flag with the Confederate flag on it with an even more Confederate flag, but because few seem to care about history or pay attention, nobody seems to get offended. The beauty of code is that it can be defended and debated. A circle of thirteen stars on a blue field? Georgia was one of the original thirteen colonies. That there also happened to be thirteen Confederate states is just a historical coincidence and if the flag is almost identical to the Stars and Bars, that apparently is just coincidence too.

This Confederate code has played out in Missouri in quieter ways. I have met southern partisans from Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas and Georgia at different times in my life. All of them have been white males, and all of them have made some kind of “Heritage not Hate” argument about their beliefs. Some of these individuals were outspoken racists, but most avoided the topic of race altogether or maintained that race — or more specifically, that slavery — was in no way the cause of the Civil War. The one thing that united them is what unites the South in general: apparent clarity. This claim may sound surprising, but white southerners have their clear definitions of what is southern and what is not. They are sure; they have rules, and they have accents. They can identify one another, and they differentiate those who are not of them. Missouri as a border state has never had this clarity because it was debated and divided, but I have met southern partisans here, and they are different from others.

The first feature is that they are outnumbered and they know it: Missouri has two large urban centers of St. Louis and Kansas City that are decidedly not politically Confederate in orientation. If you go to Virginia, Confederate markers are everywhere; even the relatively liberal college town of Charlottesville has a large equestrian statue of Robert E. Lee. In Missouri, it is subtle, for any sign of Confederate flag waving literally or figuratively will draw negative attention. The southern partisans I have met in Missouri are all “Quantrillites” — that is, they defer back to the guerilla movement rather than to the organized Confederate forces of Missouri. They will cite not inaccurately the depredations of the Union Army and Kansas forces on their ancestors’ homes and properties. They also will justify actions such as the burning of Lawrence as an act of self-defense though even the Confederacy of the time found the act objectionable.

The border war was vicious, and bad feelings still linger, yet with code, hiding in plain sight is simple. I saw a personalized license plate in Missouri that read QNTRLL. What does that mean? Support for slavery? Support for burning Lawrence? Support for guerilla war? The ambiguity is what allows it all to stand and continue without retaliation or response. Go to grocery stores in Missouri and look in the condiment sections. You might find “Old Missouri Bushwhacker Brand Premium Jalapeno Pepper Sauces from Missouri.” I have only tried “General Shelby’s ‘No Surrender’” sauce, but the hottest flavor apparently is “Jayhawker’s Hell.” The brand is produced by Little Dixie Harbour LLC. They don’t sell any sauce to stores in Kansas as far as I have seen.

I come to all of this from convolutions in my own family’s history. My great-grandmother’s family was from Morgan County, Missouri, and a relative of hers, either a father or an uncle served with the Missouri State Guard, the pro-South militia commanded by General Sterling Price, the Missouri general who was later immortalized in literature as the name of Rooster Cogburn’s cat. We have this relative’s discharge papers for 1861 from the Morgan County Rangers. If he ever served again or for whom is unknown. Mark Twain also served briefly with a Confederate company only to flee to Nevada and by default joined the Union side. Another distant relative of mine apparently was the only survivor of a Jayhawker attack, but the story is so apocryphal and shrouded that it could have been the other side doing the burning. I know little except that on that side of the family they were Southerners, or at least considered themselves to be so; the stories are just fragments because the family became fragmented.

This broken family history made me explore the Missouri Confederacy and since literature of the border had leaned south, and I decided to start writing a novel based on one of Quantrill’s Raiders, except I placed my protagonist in Colorado after the Civil War. I thought it would all be easy. It isn’t. I keep writing. Writing about the past and not messing it up altogether is very difficult; maybe we can’t blame the movies for their liberties. We don’t even understand yesterday so trying to grasp actions over a century old is fraught with peril.

But trying to address the past through fiction makes you read unusual books and go to unusual places. I visit random historical markers and battlefields; I walk in Missouri cemeteries looking for clues. In one cemetery in Jefferson City, I saw code at its most profound.

I went to an unknown grave with a large obelisk, and it turned out to be the last resting place of General John Marmaduke. Confederate General John Marmaduke, who in his postwar career died in office as the 25th Governor of Missouri. This fact is in itself may not be that significant, but at the foot of the grave was a small nylon flag. It was a flag I had never seen before. It disturbed me immediately: it featured a white cross on a blue field with a red border, and I thought it might be a Klan symbol. There was one other that I saw in the cemetery at the grave of a Confederate colonel. There were other Confederate soldiers buried in the cemetery, but only these two high-ranking officers got flags. When I looked at the flag it was obvious that a meaning was intended, but what it was, was not fully articulated, or at least not to the uninitiated. The flag seemed to say: “ I know what I am, but you don’t, and this is all intentional.”

Of course, I had to find out. I was traveling west from Jeff City and stopped at the Lone Jack battle site on the way back to Kansas City to ask them. I thought they had to know, so I drew a picture of the flag I had seen. The volunteer there didn’t recognize it, but I saw a photograph on the wall of another grave decorated with the same, small flag. The decorated grave belonged to Cole Younger, partner of the James Brothers and survivor of the deadly raid on the Northfield bank in Minnesota. When I showed the volunteer at Lone Jack the flag in the picture, he thought that it might the flag of the Missouri State Guard. I then bought a Rooster Cogburn t-shirt there, since the Battle of Lone Jack was where he lost his eye. As far as I could tell, they preferred the John Wayne version.

I wanted one of these flags, for I thought if I owned one, I would break the code fully. I went to All Nations Flag Company in the River Market to see if they had them. They didn’t. They hadn’t seen one. Whoever had them must have had them custom made. So someone is out there, having specialty historical flags made and placing them on the graves of name-brand Confederate veterans in Missouri. It’s not stupid; it’s subtle. None of the controversy of the Confederate flag remains with this grave decoration, but the intention is the same. The graves are marked, and memory is observed all with limited notice and no opposition. Code.

Part IV: Irony?

Americans are a mythological people. We believe in grand abstractions because they are what allow us to survive as a nation. We figuratively embrace ideals we cannot touch like freedom, liberty or the pursuit of happiness. The vagueness and intangibility of these terms allow us to fill in our own blanks. We survive by grudgingly allowing others to make their own definitions- a purposeful apathy known as tolerance that keeps us from erupting into civil war despite our potentially virulent disagreements. We debate what right we have to think certain thoughts or say certain things; we allow cultural disobedience as long as we believe it does not go too far. As a result, Americans are usually metaphorically black or white in orientation; we dislike shades regardless of our political affiliations. We can hate each other more easily as long as we do not have to interact and recognize our commonalities. We are complex, but it is politically expedient not to examine how or why.

As a result of our mythological needs, we as a people aren’t generally good at irony, which is a debate between appearance, reality and meaning. An intended meaning in opposition to an actual reality, or something of that nature, since irony itself is a debated term. Still, sometimes irony best appears by accident through the movements within time and space, and Forest Hill Cemetery may prove to be an example of the accidental irony of history as it plays out on a landscape.

At the entrance to the cemetery is a marker describing the end of the line of General Jo Shelby’s Iron Brigade. Forest Hill was then the farthest point east of Shelby’s Confederate forces that strung out apparently all the way to State Line Road. It would be the last real stand of the force in Missouri. Ever after, they would continue to be pushed south until there was no place left but Mexico. Is it ironic that Shelby himself would be buried up the hill from his last stand along with some of his men? Maybe coincidence is the better term, but it seems insufficient.

If there is irony at Forest Hill, it may be the presence of a resident who would not have been allowed in the cemetery at its founding. He would have been excluded due to his skin color, but this segregation was no novelty to the man, for exclusion due to melanin was standard throughout his life. Some have argued that he may have been the greatest baseball pitcher of all time, but we will never know for certain since when the records were originally kept, he was not allowed to play major league baseball though he was a giant of the Negro Leagues. His significant distinction was that he was the oldest rookie of all time when he entered the majors. He was 42. His name is Satchel Paige.

He is still segregated at Forest Hill, but apparently more due to his exceptionality than any other issue. He has a small island in the road, occupied only by him and his wife Lahoma. If you go to visit you will see some of his words and philosophy. The grave of Satchel Paige teaches that the “Social Ramble Aint Restful,” and this observation seems reasonable. His autobiography, “Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever” reads like the report of a superhero with a strong sense of humor. His story seems utterly mythical: from killing birds in flight with a rock as a child, to using a secret snake oil potion given to him by Indians in North Dakota to keep his pitching arm loose, to allowing a hit from the young Joe DiMaggio, who took it as a sign that he would be just fine in the Yankees if he got one from “Ol’ Satch.” When you read him, you believe him. Nothing seems improbable in his description of himself which sounds like what would have happened if Homer’s Odysseus was born black in early 20th century Alabama and happened to discover the sport of baseball. What gnawed was the injustice of his record not being known, that his legend was wrapped in the Negro Leagues until the majors grew large enough to accommodate him. By then he was baseball’s oldest young man.

He was not the first to get in. That he was preceded by his fellow Kansas City Monarch, Jackie Robinson, a young unknown compared to the great Satchel, truly seems to have pained him. He was the one white fans had come to see; he was the one white players wanted to face on the mound. No matter. The man had a professional pitching career that lasted almost 40 years. He was the first African-American pitcher in the Hall of Fame.

Fans come from all over to pay their respects. They often leave baseballs behind on his grave. The last time I went, I counted seven. In The Hero and the Blues, the great writer Albert Murray describes the role of the hero in reference to the blues idiom. Murray is tenacious in his contention that the African-American narrative in this country is not one of victimhood but one of adaptability and creation. He offers a description of heroic tendencies that sound a lot like Satchel Paige: “No master craftsman ever really learns everything about his line of endeavor, of course. Even at best his applications are still only a form of practice. He is a practician and follows his trade. The exceptional degree of expertise he does develop, however, not only qualifies him to function on his own, but also enables him to extemporize under pressure and in the most complicated circumstances. Nor is a higher degree of erudition and skill possible, or even relevant. Improvisation, after all, is the ultimate skill.” Though Murray is generally concerned with music and literature, improvisation seems key to pitching. Every ascent upon that small mound requires adaptability, for each batter must by definition be different. Each pitch was improvisatory, all ruled by the principle that defines great pitching and great artistry: control. Paige wanted to be in before Jackie Robinson, but even his later arrival is no small accomplishment. He claims that he was not the first in, but that he was the one they were all waiting for. It is hard not to believe him.

In the end, he won. The Confederates rest up the hill, along with the graves of famous Kansas City families, but Satchel Paige is without doubt the most famous of the dead at Forest Hill. Even the name of “No Surrender” Shelby pales in comparison. Paige’s grave remains visited while the others stay relatively barren.

What would those Confederates think, buried a few yards from a man of color, whose name outshines theirs, whose accomplishments still distinguish him, while they languish in the memories of a few? What would they think of the fact that in the 20th century, when W.E.B. DuBois would claim that the problem of the century was the color line, that their memorial would be on the wrong side of it? They are technically east of Troost, the traditional line of racial demarcation in Kansas City. The memorial to the Confederate Dead then, east of Troost, seems forgotten by all but the faithful, who do their own acts of remembrance quietly and in apparent secrecy. And Satchel Paige lies topographically below them but in still greater prominence. Time hopefully resolves these inconsistencies that may haunt us. Resolution may just be memory loss, a convenient oblivion that erases the past as it no longer fits the stories we want to tell. Or it may be possible that the stories lie side by side figuratively just as they do in actuality, in the ground at Forest Hill.

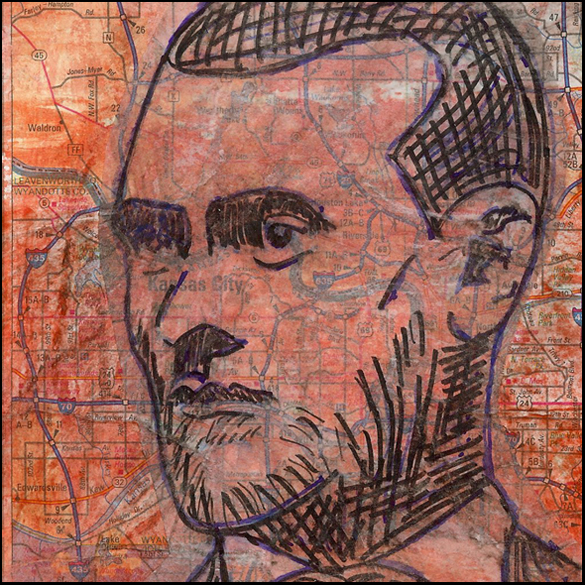

Artwork by Matthew Brent Jackson

Photos by Jennifer Wetzel

- Daughters of the Confederacy memorial, 55th and Ward Parkway

- Close up of Daughters of the Confederacy memorial, 55th and Ward Parkway

- Historical marker at entrance to Forest Hill Cemetery

- Flowers at Forest Hill Cemetery, Kansas City, Mo.

- Leroy “Satchel” Paige headstone, adorned with baseballs

- Satchel Paige grave site, Forest Hill Cemetery

- Confederate memorial, Forest Hill Cemetery

- Tombstone of General Jo Shelby

- Confederate memorial at Forest Hill Cemetery

- Confederate memorial at Forest Hill Cemetery

- Tombstone at Forest Hill Cemetery

- Forest Hill Cemetery, facing west